February 7, 2018

Plans to remove the Rome Dam will soon be complete, and work could begin as soon as next year. The deconstruction process could take three to four months, from mid-summer into fall, when water flow on the Ausable River is typically at its lowest. The cost will be paid by federal funds awarded to the Town of Jay by the Governor's Office of Storm Recovery, part of the Community Rising process designed to ensure greater flood resiliency after Tropical Storm Irene.

The dam's removal will be a major engineering project, as was its construction, yet many residents of the Ausable valley who don't live in Au Sable Forks have never seen it. They may wonder where this Rome is, and why it's dammed? When I first asked, several years ago, a neighbor in Upper Jay assured me it was once the Italian district of the Forks. I now suspect he was pulling my leg. The name turns out to be a WASP joke, since a family named Pope (no relation) lived up that way, way back when, at the western edge of the Forks, and the road to their house—now Church Lane—was dubbed the Appian Way. From its beginning on Main Street, alongside the Catholic church, Church Lane parallels the West Branch of the Ausable upstream; it turns into Ausable Drive at the last cluster of houses in the hamlet, then winds through AuSable Acres.

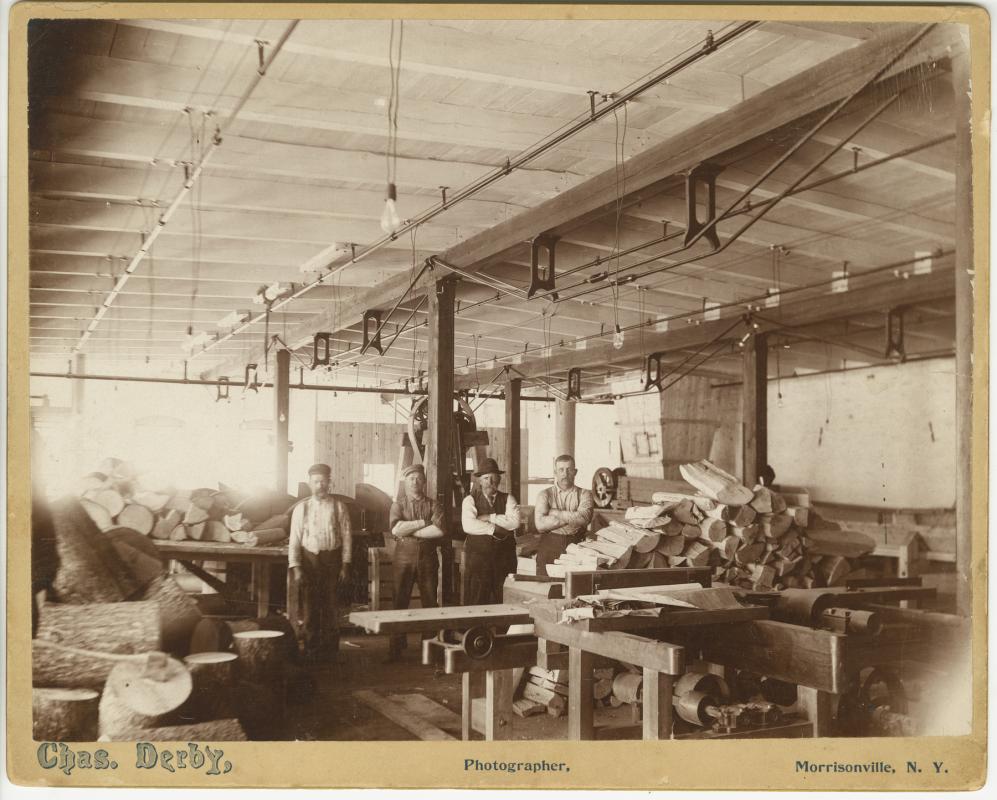

Soon after Church Lane becomes Ausable Drive, in a bedrock gorge tucked in the woods, sits a stone and concrete dam, nearly 40 feet tall and just over 100 feet wide, built in 1893 (and rebuilt in 1936) to power the J. & J. Rogers Company's pulp mill, the first phase in its papermaking process. The pulp mill stood just downstream on the right bank, as one looks downstream; only a pile of rubble remains, on private land, to mark the site. The dam also sent water to a paper mill, built across the river and farther downstream in 1902. This mill still stands, albeit in ruins. Portions of the steel penstock pipes, over seven feet wide, that carried water to these mills still line the river on either side.

Along with some 19 acre feet of water (acres filled one foot deep), the dam currently impounds 30 acre feet of sediment (more than 3,000 dump truck loads), according to the water resource engineers from the firm of Milone & MacBroom who studied the site last year and are now designing the dam's removal. They believe this represents roughly five years of sediment, from sand to boulders, blocked from moving downstream. That rivers move sediment, as well as water, is a basic fact of hydrology demonstrated by the unmistakeable sound of a flood on a steep mountain stream: beneath the roar of rushing water, the clack of boulders rolling, a grand game of pool. Some sediment goes over the ogee-curved spillway in heavy floods, but immediately downstream the river is starved of sediment—"bony," in the language of anglers and river scientists. Roughly a year's worth of sediment will be allowed to move downstream during the dam's removal, which will help to restore the channel. One goal of the planned removal is to avoid a sudden release of all the sediment, which could fill the channel and force the river to move sideways, endangering houses and other buildings. Another basic lesson of river science is that rivers move, snake-like, and it is only human infrastructure, or topography, that pins them in place, or tries to.

The State of New York—through the dam safety arm of its Department of Environmental Conservation—has deemed the Rome Dam a "high hazard," meaning that its failure could result in the loss of life. The dam is also rated as structurally unsound, meaning the integrity of its deteriorating foundation is unknown. These determinations required the Town of Jay, which owns the dam, to remove or repair it, or else face stiff fines. One side of the dam is pulling away from the rock wall of the gorge into which it is built, and it has been decades since the gates designed to release water into the penstocks opened. Buildings that once stood on either abutment are long gone, as is the cable bridge that allowed workers to cross back and forth. The dam has probably seen no maintenance since the Rogers Company went out of business in 1971—perhaps not since the pulp mill closed some fifteen years earlier, soon after the company was sold out of the family.

There has been concern in the Forks about whether the dam's removal might increase flooding, since some residents believe it protects them from flood waters and ice jams, breaking up ice as it cascades over the spillway. The engineers believe bedrock drops currently submerged in the gorge will break ice naturally, and the amount of water passing downstream will not change, after the dam's removal. What everyone wants to avoid is an unplanned breach of the dam. As Roy Schiff, the lead engineer on the project, put it, "The dam's coming down, it's just a question of when." He recently helped to engineer the removal of a smaller timber dam in Willsboro, which also powered a pulp mill.

Jay's Town Board voted to remove the Rome Dam this spring. Bids for the process will soon be solicited from contractors. AsRA is helping to obtain the necessary permits from the Adirondack Park Agency and the Department of Environmental Conservation and working to make sure the result is a free-flowing river, safe for trout and people.

James Rogers Jr.’s photo of his new dam, made with an early Kodak soon after it was built in 1893.

The J. & J. Rogers Company put Au Sable Forks on the map and employed the community for over a century. Making paper from wood pulp was its second business; iron was its first. The company was formed in 1870, though the partnership between the brothers James and John Rogers began in the 1830s and became one of the largest of several businesses extracting and processing iron ore in the Ausable valley. The company owned land throughout the valley, since forging iron required vast quantities of hardwood timber to produce charcoal. A forge might deforest 1,000 acres in a year, and the company ran ten forges in its prime.

The Rogers Company owned and cut mountainsides in Keene Valley and Wilmington (they owned much of Whiteface Mountain and lumbered it twice before selling it to the State); its vast land holdings also included Fern Lake, Silver Lake, and Taylor Pond. AuSable Acres was developed on former Rogers Company land. The company ran logs down both branches of the Ausable, controlling the flow of water with dams at the headwaters of each branch, at Lower Ausable Lake and South Meadows, as well as Marcy dam. "The J. & J. Rogers Company was a big part of why we have an Adirondack Park," acknowledges Jim Rogers (James Rogers III), a descendant of one of the company's founders who lives in Lake Placid.

By 1889, iron had ceased to be profitable in the Ausable valley. This happened suddenly, for several reasons, including the discovery of iron in the northern Midwest, the development of cheaper manufacturing processes that allowed the use of lower grade ore (most Ausable valley iron was quite pure), and the relaxing of tariffs that prevented the importation of iron from other countries. Unable to make money, the Rogers Company shut down, and Au Sable Forks, a company town, was out of work.

At the time, James Rogers Jr. controlled roughly 75,000 acres of timberland on which much of the hardwood had been cut. He had a willing workforce in the community his family helped to establish at the confluence of the river's two branches, and felt an obligation to employ these men. A business opportunity occurred to him: harvest the remaining softwood, mostly spruce, for wood pulp, the new way of making paper. This initiated a new era of logging in the valley, cutting trees at higher altitudes, along the river's tributary streams, while continuing to use the river as a highway to bring logs downstream. The mills he designed and built, first the pulp mill, then the paper mill, together served as a transformer, turning a prolific raw material into an industrial product, using water power from the river to fuel the process at every turn. This process transformed the landscape as well, as the iron industry had before it.

Jim Rogers, who with his cousin John might have taken over the family business—run in their childhoods by their fathers and grandfather (grandsons and son of James Rogers Jr.)—still regrets its sale out of the family in the mid-50s. This occurred when a cousin who had become the majority shareholder sold his shares to an outside buyer, with little concern for the company or the community. The pulp mill was soon ruined, when the new owner, a holding company in New Jersey, tried to convert it from the sulfurous acid process to the ammonia process, blowing the valves that held the cooking liquor under pressure as it reduced wood chips to pulp. The Rogers Company had been buying wood from local suppliers since the last log drive came down the Ausable in 1923; now it had to buy pulp from Canada. Jim Rogers speculates the company's last owner had less interest in making paper than in what remained of its extensive land holdings. He wishes it had been sold to Hammermill, which came in with a lower bid, believing it might still be in business had this happened.

The Rogers Company shut down in 1971 for several reasons: orders were down, and the State of New York required it to build a water treatment plant it could not afford (the State would have contributed a significant portion of the cost) to avoid the continued dumping of toxic paper byproducts into the river. The main stem of the Ausable, below the Forks, turned different colors depending what color paper was being made. Sharron Hewston, Jay's town historian, likes to tell how, the first time red paper was made, "The people in Keeseville thought there had been a massacre!"

Jim Rogers believes the underlying causes of the company's failure were financial mismanagement and poor quality control in its final years. This is a regret, not just because Au Sable Forks has not found a comparable employer in the decades since, but because the J. & J. Rogers Company was in many ways a model business before its sale, innovating in both its process and its products. His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were all skilled, if largely self-taught, engineers, who designed their mills to maintain their community in a remarkable case of what Philip Hardy, in his history of the Rogers Company, calls "paternalistic capitalism."

J. & J. Rogers Co. pulp mill in 1903, the year the paper mill opened across the river. Note the dam in the background and the massive pile of logs between it and the mill.

Roy Schiff and Brian Cote, the engineers who have studied the site of the dam, probing and modeling the riverbed below the impoundment, believe the dam's removal will reveal a beautiful natural gorge. The water level will drop inside the impoundment, exposing land no one alive has ever seen.

Documenting the site before this happens, and researching its history, are important steps in the removal process so that evidence of this business which shaped the local landscape and community survives. The photographs accompanying this story are from the Rogers family archive. Together with contemporary photographs of the site, some of these extraordinary images will be exhibited in Au Sable Forks in the near future. Those with memories of the Rogers Company they would like to share are encouraged to contact the author in care of AsRA.

Written by Stephen Longmire. Stephen is a landscape photographer and historian who lives in Upper Jay. He is documenting the Rome Dam prior to its removal.